A Story ARC: How I Found God, Got Religion, and Stayed an Atheist

And no, my God is not Jordan Peterson!

It was Buckminster Fuller who said:

"You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete."

The founders of the Alliance for Responsible Citizenship (ARC) understand this truth, and it drives their mission to create a better story around which Western civilization can be revitalised.

I have just returned from their conference at London’s Excel Centre and need to process my thoughts. So, here is the first in a series of articles. In each one, I shall offer a solution to a problem identified at the conference.

A Question of Faith and Modernity

Michael Shellenberger’s talk about AI contained a slide that resonated deeply with me. It made me think of Fuller’s insight and how, thirty years ago, I—a committed atheist—chose to be married in a church without compromising my principles.

G.K. Chesterton was right when he observed that people will believe anything when they stop believing in God. But if the traditional religions of old are at odds with modern sensibilities, how do we discard the scummy bathwater while preserving the baby? How do we keep God so as to avert the moral decline highlighted by Shellenberger?

Some assume that belief in God requires slavish adherence to one or other of the published religious doctrines. This is not true. The moral crisis stemming from the decline of religion is real, but it does not have to be. It is possible to embrace the ethical and communal benefits of religious belief while maintaining a commitment to reason and science. If the God of Judaism was version 1.0, and the Christian adaptation version 1.5 (now with added Jesus), then our contemporary understanding of the world demands God 2.0—an update that honours ancient wisdom while aligning with modern knowledge.

Encountering Faith Without Losing Atheism

On the first evening of the conference, I found myself in a Chinese restaurant, surrounded by a group of warm and welcoming Christians. Before the meal, grace was said. My only discomfort was in being caught off guard—such rituals are uncommon in secular Britain. But this moment reminded me of my own reconciliation of faith and rationalism.

I was raised an atheist. My parents instilled in me a strong moral compass, rooted in the cultural Christianity that defined England in my youth. As a child, I recoiled at certain aspects of organised religion—the supernatural, the authoritarian structure, the legal requirement for daily religious education in schools. And the hypocrisy of some Christians I encountered fuelled my distrust. I was bullied at school, and the bullies were, ironically, the same ones sitting in chapel.

As a consequence I developed a prejudice beyond mere scepticism that was only resolved when I was engaged to be married. Well, almost resolved, I still have a visceral aversion to men in frocks.

At school, we were taught the Ten Commandments. The second of which is:

“You shall not make for yourself a carved image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. You shall not bow down to them or serve them.” (Exodus 20:4-5)

And yet every church you could visit had people bowing down to crosses or statuettes of Jesus or Mary or both.

It’s a good job Michelangelo was a sinner.

To my teenage mind, Christianity was a system that permitted, maybe even encouraged, flouting the commandments with the promise of divine forgiveness.

A Wedding Dilemma: Can an Atheist Marry in Church?

When I met the woman who would become my wife, I realised that marriage is not just a contract but a covenant—a solemn commitment requiring deep understanding, conviction, and sacrifice. The UK civil ceremony lacked the gravitas I needed to make such a commitment. If we were to marry, it had to be in a church.

But how could I do this without becoming the hypocrite I had spent years despising?

Fortunately, 1993 provided an answer. That year, Anthony Freeman, an Anglican priest, published God in Us: The Case for Christian Humanism, arguing that God is not an external being but a human construct—a metaphor for the highest ideals of humanity. Armed with this perspective, we approached our local vicar, Stephen Terry of St. Philip’s in Hove, and explained our position. To our relief, he embraced our honesty, and together, we crafted a service that respected both tradition and belief.

For this to work, I needed to construct a meaningful concept of God—one that I could genuinely swear upon when taking my vows. So, I embarked on a mission to define what ‘God’ meant to me.

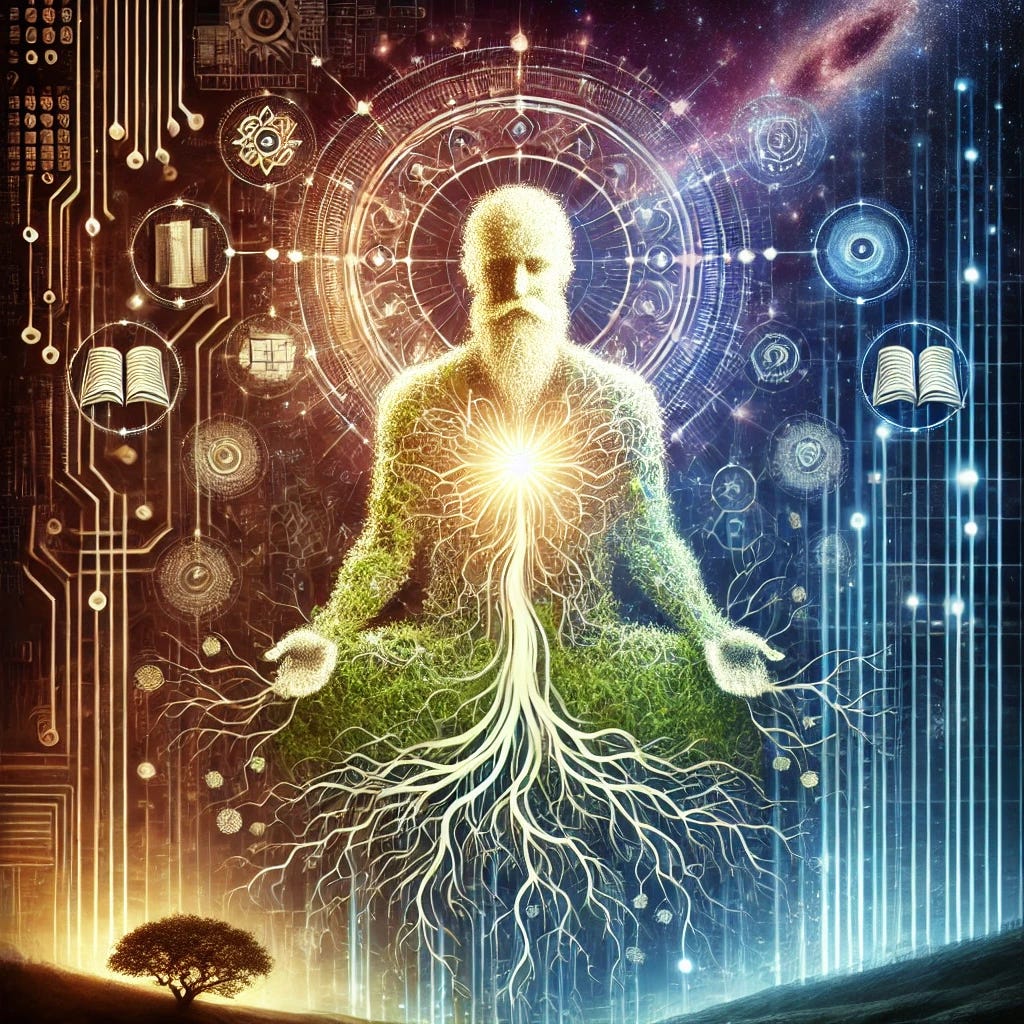

Introducing God 2.0

After much reflection, I arrived at my own holy trinity: Luck, Nature, and the Collective Wisdom of Mankind.

Luck: Life is inherently unfair. Some are born into privilege, others into hardship. Circumstances can change in an instant—be it a stroke of misfortune or a lucky break. While we cannot control luck, we can influence it by working hard, taking calculated risks, and forging connections.

Nature: The universe operates by its own laws, indifferent to human desires. From the principles of physics to the processes of evolution, nature sustains us, and understanding its workings is essential for progress.

The Collective Wisdom of Mankind: Humanity has spent millennia accumulating knowledge, building civilizations, and developing ethical frameworks. The ARC conference itself highlighted this, with its exhibition featuring The Syntopicon—a compendium of 102 ‘Great Ideas’ drawn from history’s greatest minds.

This trinity became my version of the divine. So, when I prayed for my mother’s cancer to be cured, I was appealing to all three elements: luck, in the hands of fate; nature, in the resilience of her body; and human wisdom, in the skill of her doctors.

When we give thanks to God for our dinner, we are thankful for the luck involved in a bountiful harvest provided by nature and the accumulated wisdom of the farmers, food logisticians, and chefs.

A Model for the Future

At ARC, Shellenberger pointed out various societal ills that Chesterton had presaged with his diagnosis of the problem: the erosion of shared values has left Western civilization unmoored. But Jung, Fuller, Aristotle, and—if I may be so bold—I offer a solution: God 2.0.

This new framework retains the communal and moral strengths of traditional faith but updates it to align with modern understanding. It respects the narratives that have shaped our cultures while ensuring that belief remains compatible with reason.

And crucially, God 2.0 is backwards-compatible. It works within the structures and rituals already in place, bridging the gap between faith and scepticism, tradition and progress. And just like any good software, God 2.0 is open-source. Feel free to download, modify, and share responsibly.